52 Ancestors, Week 48: Tobias Finkbiner and the origins of the Finkbiner name

|

| Freudenstadt, Germany, today |

Tobias Finkbiner, was born 5 Jun 1722 in Labbronnen, Freudenstadt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

He immigrated to America in 1752, landing at Philadelphia.

He was married to Maria Dorothea Bruch in about 1753. Their son, Phillip Jacob was born in 1754.

Tobias died in Trappe, PA in June of 1775.

--**--

The Finkbiner line can be traced back to the middle ages:

“Helmut Finckbein (1907 – 1993) of Berlin Germany did extensive research. He found all the Finkbeiners in the Baiersbronn, Wurttemberg church records of family registers that began in the year 1627. He then studied the medieval records for the Allgaeu region of southwestern Bavaria where he found the earliest mentioning of our first ancestor, Hans “der Fintboner.”

“During the Middle Ages (approximately from 1100 to 1500 AD) Germany, Austria, and Switzerland were part of the Holy Roman Empire ruled by the Hapsburg family of Vienna, and the populace adhered to the Roman Catholic faith. During this time, the German people of noble and influential means began taking on surnames to distinguish one family from another.

However, most of the peasants living in the rural villages and towns during Medieval times were held in bondage to feudal landlords and vassals and therefore did not possess surnames. Such was the case of our ancestors until the late 1300s when our earliest known ancestor cunningly obtained his freedom.

This ancestor, known originally only by his given name of Hans, was born near the Bavarian village of Memmingen around the year 1340. He was a bondsman of the feudal lord or patrician Heinrich Kuntzelmann of Augsburg, who owned vast expanses of land in the Allgaeu.

Nothing is known of Han’s early life, although his childhood occurred during the time of the dreaded Black Death (Bubonic or Great Plague) that killed almost half of Europe’s estimated population of 95 million between the years 1347 and 1352.

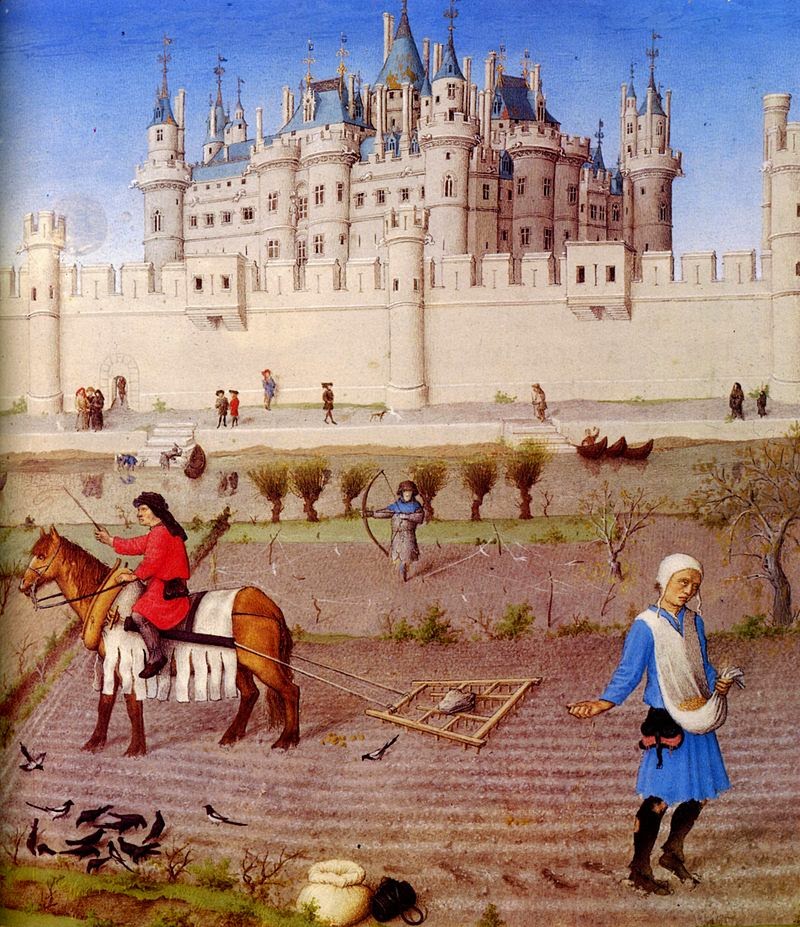

|

| The peasants preparing the fields for the winter with a harrow and sowing for the winter grain, from the The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry, c.1410 |

When he became old enough to work the fields, Hans duties as a peasant serf were to cultivate beans (a bean farmer in German is “ein Bohner”). Beans were the principal staple crop of Europe.

One evening in 1369 after a grueling day in the fields, our ancestor Hans and his overseer Hans Brockhardt decided to celebrate their accomplishments by partaking of German liquid bread (beer).

Overseer Brockhardt, was a freeman being paid by Kuntzelmann to manage his property of both land and men. Brockhardt held the serf Hans in high esteem for his hard working ethics and knowledge of bean cultivating and subsequently befriended him.

However, unknown to Brockhardt was that the serf Hans had been planning his escape upon the Overseer reaching a state of stupor from drinking beer. While Hans Brockhardt slept off the effects of the beer, the serf Hans made off to the market town of Kempten on the Iller River, located approximately 20 miles south of Memmingen.

|

| Kempten, today |

For the next several years, our ancestor Hans lived in Kempten as a free man working as a paid “bohner” (bean farmer) without Hainrich Kuntzelmann’s knowledge of his whereabouts. Hans soon adopted the surname “der Boner” in honor of his occupation and apparently became a citizen of Kempten sometime in early 1372.

Also living in Kempten at this time were some of Hainrich Kuntzelmann’s relatives, including his brother-in-law Burcken Knopf and a cousin named Jacob Kuntzelmann, who was elected Buergermeister (mayor) of Kempten in 1389.

Burcken Knopt eventually learned of Hans’ identity and informed his brother-in-law of where Hans was living. Since Hans had earned a solid reputation as a knowledgeable bean farmer, Hainrich Kuntzelmann traveled to Kempten by horseback to fetch back his bondsman.

Upon entering the town’s market square on Saint Michel’s Day (Sept 27th) of 1372, Kuntzelmann presented his spear and shield bearing his coat of arms consisting of a black eagle seal and demanded his bondsman be returned to him by calling out:

Hans! Hans der Fintboner! Meines Eigenmann gibt sich zu mir!”

(Hans! Hans the found bean farmer! My bondsman, give yourself to me!”)

However, Buergermeister Jacob Kuntzelmann informed his cousin that under the governing justices for Kempten, Hans was now a free man and a citizen of Kempten. Realizing that he would not get his bondsman back, Hainrich agreed to release any hold he had on Hans in exchange for 35 guilders and a signed a document acknowledging this agreement.

The previously mentioned document, the original which exists to this day in the Public Office Archives found in Munich, was the earliest written document Helmut Finckbein had discovered mentioning our forbearer.

As a result of the encounter with Hainrich Kuntzelmann, the townsfolk of Kempten began referring to our ancestor as Hans “der Fintboner” which he eventually adopted as his surname. Three other men are named in Kempten’s records during the late 1300s as possessing “der Fintboner” surname: namely, Hainrich, Bentz and jung (young) Hans. We assume that these three men were sons of our Hans.” (1)

(1) Finkbeiner Family Newsletter, August 1997, by Gary A Finkbeiner

Fascinating how surnames came into existence and how the name Finkbiner from der Fintboner or ein bohner (bean farmer) quickly became a surname that would last going on seven hundred years without much further substantial change.

ReplyDeleteThe folk etymology of 'der Fintboner' doesn't stand up to the slightest scrutiny. Also, the details of Hans' escaping the bonds of Kuntzelmann are complete fantasy.

Delete